Android Accessibility Services was created to help developers enhance their apps to cater to and assist individuals with disabilities in overcoming their challenges when using their smartphones. When users download these apps, they need to enable ‘Accessibility Permissions’ in order to take advantage of these benefits.

For example, if a developer is concerned that some text may be hard to read for vision-impaired individuals, they can use the service for reading the text to the user out loud.

The individual has to allow the app to take over its device by granting it “permission.”

Although these “special” apps help alleviate many hardships for millions of people, allowing accessibility permissions to these apps and other opens the doors to an array of possible cyberattacks, putting the device owner at a financial and personal risk (discussed further below).

Examples of Android Accessibility Service Apps

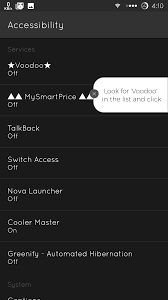

The below image conveys the Android Accessibility permissions page:

You can see in the above image an app called TalkBack. TalkBack is a screen reading utility for individuals who are blind or visually impaired. The user performs input via swiping, dragging, or an external keyboard. The output is talking feedback. It even assists color-blind people to distinguish between different commands (i.e-such when red represents “stop,” and the green represents “go”) as it gives descriptions of the colors.

Allowing an app to take control of your device can be quite dangerous. When an application has greater access to one’s mobile device, security gaps are broadened. By permitting the app to take full control over your device, you can potentially, unknowingly, allow malware to access your device and take control over it as well. When the malware enters your device, it can steal sensitive information about you, such as banking information and personal information.

Malware uses clickjacking, or the process of hijacking a user’s click on their computer, to grant itself access to a person’s device by showing them an image controlled by an intruder urging them to click it. Once the user clicks it, they grant access to the hacker. The user thinks they’re clicking a legitimate button when in fact, it is a fraudulent link. This scenario can be dangerous when the fake webpage/image presented to you depicts an action that requires the insertion of sensitive information, such as your credit card details or your password. The hacker can then steal that information and use it.

Cloak and Dagger attacks allow hackers to take full control of a device. They do so silently as they steal private data, including keystrokes, chats, device PIN, online account passwords, OTP passcode, and contacts.

The issue with this kind of attack is that it uses legitimate Android Accessibility services, so getting past security detection is easy. It allowed developers to upload infected apps to the Google Play store, and as a result, unknowingly spreading the malware.

Banking Trojans, such as Anubis, works by stealing banking credentials from users.

Traditional banking Trojans fool users by showcasing a fake overlay that looked like a banking app. As a result, the users entered their banking details into the fake bank rather than the official app.

With Android Accessibility Services, Anubis skipped this step and was able to read what people were typing on their keyboard using a real banking app.

Ginp is an Android Trojan similar to Anubis. It’s masked as an Adobe Flash Player that the user installs on their device. It then asks for permissions, one of which includes Accessibility Services. If the user permits, the hacker behind Gimp gains admin privileges, which would allow him to send SMS messages, access the contact list, and forward calls.

Following the appearance of the malware mentioned above in Android Accessibility Services devices, Google decided in 2017 to delete any apps on the platform of Accessibility Services that don’t help the disabled yet ask for accessibility permissions. However, this didn’t stop the scams.

Android users can download apps from the Play Store, a more secure space, but also[WU1] third-party stores, which are not as monitored and scanned for malware as the Play Store.